ÇATALHÖYÜK 2003 ARCHIVE REPORT

|

EXCAVATION OF THE 4040 AREA

Joann Lyon & Jeremy Taylor

Contributions by Jon Sygrave and Ulrike Krotscheck

Cambridge-Stanford Team

Supervised by: Joann Lyon and Jeremy Taylor

Site Assistants: Reed Adam, Pia Andersson, Serdar Cengiz, Eda Cizioglu, Dan Contreras, Güner Coskünsu, Cassandra Cueller, Raksha Dave, Bleda During, Vahit Tursun, Günes Dürü, Gudmunder Jonsson, Hüseyin Kamalak, Ulrike Krotscheck, Asli Kutsal, Sophie Lamb, Jon Sygrave, Ali Türkcan, Emma Twigger, Nathanial Van Vallkenburgh (Parker), Selcen Yalçin, Lisa Yeomans, Mehmet Yürük, Candemir Zoroglu.

Abstract

Between the 1st of July 2003 and the 14th of August 2003 an international team of archaeologists conducted an extensive surface excavation of an area measuring 40m by 40m to the north of the East mound of Çatalhöyük. The aim of the seasons work was to expose, through surface scraping, the underlying Neolithic and later deposits similar to the work conducted in 1993 –94 (Matthews, R. 1994). The excavation was therefore intended to both compliment and add to the earlier ‘scrape area’, carried out just to the north of the 4040 area. Only limited and localised excavation took place, the main aim being to map archaeological deposits and create an overall plan, with the intention of identifying possible areas for focused excavation during forthcoming seasons. For this reason interpretation and dating of any archaeological features must be seen as provisional.

The investigation revealed a range of different archaeological features, which are thought to date mostly to the Neolithic with some Classical, Byzantine/Roman or Hellenistic periods represented. A number of burials were exposed, most of which were single interments of late periods at random locations across the area, but a few were also Neolithic.

Post-Neolithic structures were exposed at the crest of the area towards the west and southwest of the 4040. The most complete building measures14m square, numbered Building 41. The structure was identified by a series of wall foundations and associated wall collapse along the building’s eastern outer edge. Five spaces were identified within Building 41 with traces of a hard gypsum-type plaster floor in 2 small rooms. The overall plan of the Neolithic buildings, especially when linked up to the earlier scraped area appear to define ‘sectors’. Houses were as usual tightly packed together but groups of buildings seem to have been defined by at least two linear open areas of varying widths, that have been referred to as possible ‘streets’ or alley ways, running east–west. They seemed all directed towards the top of the mound. But instead of these alleys leading to public or ceremonial buildings, the top of the mound seemed to have been primarily used for refuse discard or midden.

Özet

1 Temmuz ve 14 Agustos 2003 tarihleri arasinda uluslararasi bir arkeoloji ekibi Çatalhöyük’te Dogu höyügün kuzeyinde 40 x 40 metrelik bir alan üzerinde genis çapli yüzey kazilari gerçeklestirmistir. Bu sezonki kazilarin amaci, 1993-1994 yillarinda yapilan çalismalarin bir benzeri olan yüzey siyirmasi yöntemiyle höyügün üzerindeki Neolitik yapilari ve daha geç dolgulari gün yüzüne çikarmakti. Bu sebeple kazilarin, 4040’in kuzeyinde kalan ve daha önce yüzeyi kazinan alana (Roger Matthews, Archive Report) eklenir biçimde gerçeklestirilmesi planlanmistir. Sinirli ve bölgesel olarak gerçeklestirilen kazilarin temel amaci, önümüzdeki yillarda üzerine egilinmesi olasi bölgeleri tanimlamaya yönelik olarak, arkeolojik dolgularin planinin çikarilmasi olmustur. Bu yüzden, buradaki arkelojik ögelerin tarihlenmesi ve yorumu geçici olarak görülmelidir.

Bu çalisma, bazi Klasik, Bizans/Roma ve Helenistik dönemlerin de temsil edilmesine ragmen, genelde Neolitik oldugu düsünülen farkli arkeolojik ögeler ortaya çikarmistir. Ortaya çikarilan gömülerin pek çogu bu alan üzerinde gelisi güzel yayilmis olan, daha geç dönemlere ait tekil gömüler olmakla birlikte, birkaçi Neolitik döneme aittir.

Neolitik sonrasi yapilar, 4040’in bati ve güney-batisinda kalan bölgede ortaya çikarilmistir. En bütün halde bulunan 14 metrekarelik yapi, 41 nolu bina olarak adlandirilmistir. Bu yapi, bir seri duvar temelleri ve yapinin en dogu kisminda kalan duvar çöküntüsü ile tanimlanmistir. 41 nolu binanin içinde, sert alçitasi türü sivali taban izleri bulunan iki küçük oda dahil, 5 mekan tanimlanmistir. Neolitik binalarin genel plani, özellikle önceden yüzeyi kazinan alanla baglandiginda, belirli “sektörler” tanimlar gibi gözükmektedir. Evler her zaman oldugu gibi sikisik düzende dizilmistir. Ancak ev gruplari, olasi “caddeler” ya da “sokaklar” olarak tanimlanan ve dogu-bati dogrultusunda uzanan, farkli genisliklerdeki en az iki dogrusal açik alan tarafindan tanimlanmaktadir. Bunlarin her biri höyügün tepesine yönelmektedir. Ne var ki, bu sokalarin kamusal ya da törensel yapilara açilmasi yerine, höyügün tepesinin temelde çöp alani olarak kullanildigi gözükmektedir.

Introduction

Between the 1st of July 2003 and the 14th of August 2003 an international team of archaeologists conducted an extensive surface excavation of an area measuring 40m by 40m to the north of the East mound of Çatalhöyük. Within this report the area of excavation is referred to as 4040.The 4040 team consisted of a mix of professional contract archaeologists from the UK, and academic archaeologists and students from universities in Turkey, the UK, and other countries.

The aim of the seasons work was to remove the topsoil over the 4040 area, scrape topsoil to reveal the underlying archaeological deposits to produce an overall plan of Neolithic and later building plots. The excavation was intended to both compliment and add to an earlier ‘scrape area’, carried out just to the north of the 4040 area, during the 1993 season.

The area was divided into 5m x 5m squares and teams of 3-4 archaeologists with local workers, cleared topsoil down to recognisable in situ deposits. This exposed horizon was planned as the next square commenced. The topsoil was between 0.1m – 0.5m thick, more shallow at the crest of the area becoming thicker to the east where the mound sloped off.

During the course of the investigation it became apparent that topsoil removal alone would not be sufficient to make the boundaries of buildings clearly visible. This was because the surface of the archaeology was very eroded over substantial areas of the site. For this reason it was decided that localised excavation of eroded deposits would also take place, in order to make any structures more visible. The 5m x 5m grid squares (identified by their SW grid co ordinate) were therefore ‘re-visited’, and excavation of deposits, mostly in the form of differential erosion and compaction horizons, was conducted until building plans were clearly articulated. The investigation revealed a range of different archaeological features on the site, which are thought to date mostly to the Neolithic with some Classical, Byzantine/Roman or Hellenistic periods represented which included a number of burials. These were only excavated where they impeded the definition of structures or where the skeletal remains were exposed which would suffer further deterioration if left in situ. Burial cuts that were defined but where no skeleton was visible were left in situ for future excavation.

Neolithic Period

Neolithic period features identified on the site consisted of the wall lines of buildings and their associated internal and external features, such as hearths, floors, burials and middens. None of these deposits were excavated. Associated with these structures were single and multiple Neolithic burials, some of which were excavated in the 2003 season. Other burials were recorded and preserved in situ, with the intention of excavating them next season.

Structures and Spaces

Due to the fact that no Neolithic structures were actually excavated this season, it is dangerous to attempt to overly interpret the site, based simply on what is visible in plan. For instance, it would be simplistic and probably inaccurate to view the features currently visible as representing a single phase of activity. The first factor one must take into account is the level of erosion that will have taken place. It is probable that the site has been subject to severe erosion over the centuries, especially on the slopes of the mound, which means that multiple phases of building will have been simultaneously exposed. For this reason a brief description and initial discussion of the sorts of deposits encountered now follows.

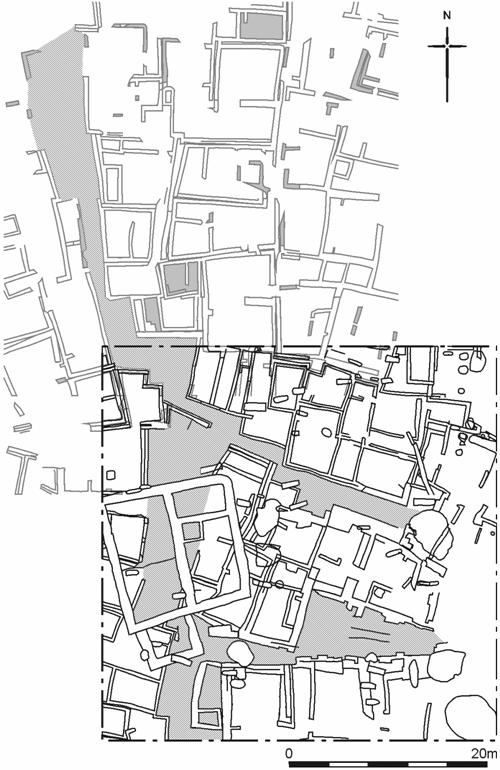

The overall plan of the 4040 area indicates that a range of different structures and spaces are present in this area of the site (Fig. 9). There are approximately 65 internal spaces or rooms (this is an initial approximation only, and should not be quoted as definitive), visible, some of which are defined by a single mudbrick boundary wall; others are defined by double or triple walls. No assessment of the number of actual buildings present has yet taken place. Although no deposits were actually excavated, the eroded tops of clay walls were removed in some areas in order to clarify the wall lines. This process generated some finds, but the interface between the base of the topsoil and the top of the archaeology was extremely diffuse. For this reason the units created to describe this process are by no means secure finds ‘contexts’, and the means by which any finds were deposited in these units should be viewed as arbitrary. The unit numbers were issued to describe the erosion process and are the ‘bridge’ between the formation of topsoil, and the final cessation of activity on the site; they are therefore a negative category.

The overall site plan suggests that the buildings in 4040 are formed into distinct groups. These groups seem to have been defined by at least two linear open areas of varying widths, that have been referred to as possible ‘streets’ or alley ways, running east–west across the site. The first ‘street’ was visible in the northern extent of the site and was traced from grid square 1030E/1170N down to grid square 1060E/1155N (see Fig. 4), at which point it ended, changed its course, or simply became indistinct. This first ‘street’ was initially identified during the 1993 season, where it was mapped running approximately north–south across the area. The second ‘street’ became visible in grid square 1035E/1135N where it ran northwards and then turned to the east in grid square 1040E/1140N becoming indistinct in grid square 1060E/1140N. The widths of both ‘streets’ were extremely variable throughout their courses, for instance the second street appeared to measure up to 6m across in grid square 1050E/1145N, and only 0.3m across to the west in grid square 1045/1140.

It is possible that these linear spaces may have originated as access routes across the site, one possible explanation for the variable width of the ‘streets’ being that they were gradually encroached by buildings. Perhaps the original streets/external spaces were more regular in size and shape, and they began to be built over as the nature of their use changed. In the case of the second linear space, its secondary (if not primary) purpose was certainly as a midden. The entire length of the space consisted of homogenous dark grey ashy coloured material, with abundant human and animal bone, as well as pottery finds and obsidian pieces. This is in contrast to the first linear space in the northern extent of the site, which consisted on the surface of rather sterile (by comparison) dumped material, and containing no midden like deposits at all, at least in the 4040 area. The most eastern part of the first linear area was occupied by midden deposits, but these seem to be associated with a general midden which occupied the summit area of the site. Of course it is entirely possible that there are midden deposits along the entire length of the first linear space, but that they are currently sealed by dumping and collapsed wall deposits.

Figure 9: Building ‘sectors’ and possible streets, 4040 Area with 1993 – 4 scrape Area

The buildings that are defined by these linear spaces seem to be distinct from each other. The buildings towards the northern boundary of 4040, on the northern side of the first linear space, are fairly regular by comparison to the rest of the site. Their walls are mainly single, with some double walls, and the spaces they enclose are fairly regular in some cases. The buildings which occupy the central area of the site, and are defined by linear spaces to the north and south, seem to be much more robust. In particular the walls fronting onto the external spaces on each side are extremely thick, almost up to1m thick in places. Of course it is possible that these may be double or triple walls, which require further excavation to define them. The buildings on the southern side of the second linear space are also extremely robust, and have triple external walls in places.

The significance of the grouping of these buildings lies with the fact that they are not merely in groups because they happen to be separated by linear spaces. They also appear to be orientated slightly differently from one another, which implies that the grouping is not arbitrary. This has obvious implications when considering how the settlement was organised, and the amount of centralisation and planning that dictated its growth.

Burials

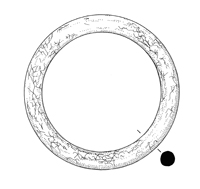

Neolithic date burials were only excavated where they were encountered eroding out of topsoil and underlying deposits, so there will be undoubtedly a greater number of Neolithic burials found during the next season. A combination of 38 single and multiple Neolithic burials have been excavated this season. One of the multiple burials (F.1202) was particularly interesting as it contained a number of grave goods including many shell beads of different size and shape, a stone, possibly alabaster, armband as well as a copper one. The presence of copper probably places the burial at the late Neolithic as hitherto copper has only ever been recovered from the Neolithic sequence in small fragments. This armband is by the far the largest copper object found which was beaten and folded (See Fig.15). Source is as yet uncertain as we await analysis results.

Burial F.1244

Burial F.1244 represents a multiple Neolithic burial apparently located in the northwest corner of a building which was visible after the removal of topsoil. The remains of numerous individuals were present in the fill although the most articulated was represented as skeleton (8813). The remains were in very poor condition and had been disturbed by late (classical) burials F.1242 and F.1402. The significance of burial F.1244, were the number of artefacts recovered from a concentrated area suggesting they were placed as a group between the head and knees of the crouched burial. These included two complete clay stamp seals of geometric design; one was closely associated with skeleton (8813) 8813.X1 and the second within the general fill (8814) 8814.X15 (see Stamp Seals below). Other material included an elongate marble(?) bead, two bear teeth, worked stone, a pre-form bone ring and bone ‘fork-type’ object (See Fig. 48). A further four beads were recovered from the flotation residue.

Burial F.1202 – Jon Sygrave

The remains of up to 11 individuals were recovered during the course of the season from an area of approximately 4m x 4m in the extreme northeast 5m x 5m square (Fig. 10). The surrounding topsoil could not be removed to begin with because the bones were within it and the limit of the burial was unknown. An arbitrary limit was established and subsequently extended before it was necessary to remove the rest of the topsoil in order for the grave to be seen within the context of its surrounding archaeology.

Figure 10: Burial F.1202

Unfortunately the number of individuals present was not initially apparent and excavation was conducted believing that one or two skeletons required excavation. However, as the upper remains within the grave were excavated more and more remains were revealed, most inter-tangled such that deeper located bones had to be released in order for upper ones to be lifted. Excavation was finally halted when a suitable horizon was reached. This complex of burials is therefore, still under excavation to be continued next season when it can be excavated within its surrounding context.

The area of the burials had suffered extreme erosion indicated by the extent of displaced and weathered surface bones prior to re burial by hill wash. The grave was also ridden with animal burrows, which may account for some of the movement and destruction of bones and artefacts within the grave. A number of the individuals excavated were associated with artefacts, mostly beads found in random location but some clearly originally strung together and associated with individuals (Figs.11, 12, 13). Plans and photographs were made of the remains layer by layer on which each bone and artefact was annotated with its own unique unit number before lifting. Descriptions of the skeletal remains (7541), (7542), (7543), (7544), (7545), (7557), (7576), (7577), (7578), (7579), (7580), (7581), (8776), (8777), (8778), (8800) remains follows (see below).

|

|

|

Figure 11: Shell (?) beads |

Figure 12: Beads in situ |

Figure 13: Beads re strung |

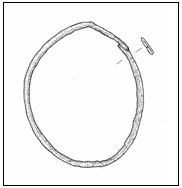

As burial F.1202 was excavated out of sequence of its surrounding context it is not possible to say for certain what period of the Neolithic they represent. Initial interpretation was based on the attitude of the burials, all being in crouched positions and the associated artefacts, although the quantity and bead-type were not common to those found in the mid-Neolithic levels (Levels VII and earlier), although similar to some found during Mellaart’s excavations in the 1960s. Of particular note were armbands found on two individuals, one was of marble or alabaster found mid-upper arm on skeleton (7580) 7580.X2 (Fig. 14), similar to one found in the 60’s, and a second was of beaten and folded copper on skeleton (7557) 7557.X1 (Fig. 15). Although copper has been found as small fragments throughout the Neolithic levels, nothing of this size or type has been found to date which possibly pushes this complex of burials to the Late Neolithic levels or even later, to the transitional Neolithic-Chalcolithic period.

|

|

|

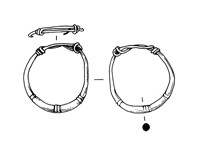

| Figure 14: Alabaster? Armband 7580.X2 |

|

|

|

| Figure 15: Copper armband 7557.X1 |

Later Periods

Post-Neolithic structures were exposed in west and southwest areas of the 4040. Partial excavation of some of these features took place in the 2003 season, and so more detailed information is available for these periods than for the Neolithic period at this stage. In addition to the structures, a number of post-Neolithic burials were also identified. These were excavated where the skeletons were exposed during topsoil removal.

Structures and Spaces

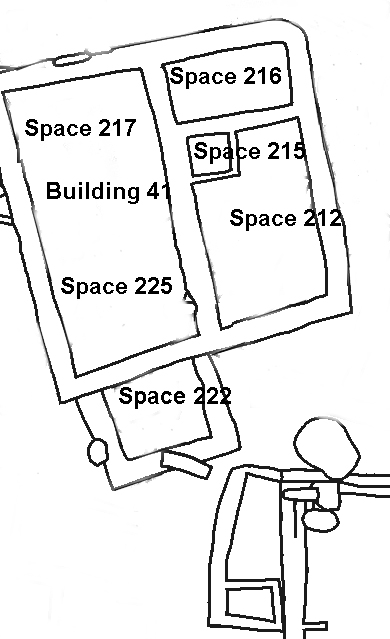

The most significant of the post-Neolithic structures identified in 4040 was an almost completely defined building measuring 14m square, numbered Building 41 (Fig. 16). The structure was identified by a series of wall foundations and associated wall collapse along the building’s eastern outer edge. Plans to excavate the wall foundations were abandoned when trial sections revealed a depth of up to 1m and a width of up to 1.25m. The foundations and associated construction cuts were numbered F.1213-4, F.1217-1220 and F.1222. Five spaces were identified within Building 41 and numbered Spaces 212, 215-217 and 225. The wall foundations collectively defined internal spaces, in the western half of the building Spaces 217 and 225 were separated by a construction cut for a ‘mud plaster’ floor in Space 217.

Figure 16: Building 41 (For scale see Fig. 4)

Two gypsum-type plaster surfaces were exposed in Building 41. In Space 215, a small room within the north-west corner of Space 212, remnants of gypsum plaster floor covered over one third of the surface area, and has been left in situ. A smaller remnant of gypsum plaster, 0.54m x 0.50m (8846), survived in Space 217 overlying the 'mud plaster' floor (described above) and was located towards its southern limit. Flecks of plaster were visible to the north of this remnant, so its original extent may have been substantial.

Other notable features within Building 41 included structural elements consisting of limestone cobbles, denoting an internal wall lining with possible associated entranceway along the western outer wall (8788), wall F.1218. Also revealed were three large cobbles possibly utilised as post packing or a post support. These were located just within the southern boundary of Space 217 (8789).

Outside the main square structure of Building 41, three walls (F.1245, F.1246 and F.1247) of similar width, but with shallower foundations, enclosed an additional area (Space 222). This may be interpreted as a later extension to the main part of the building, located to its south side and tacked on to wall F.1217.

At present Building 41 remains undated. Throughout the season the structure has been described as Classical, Byzantine/Roman or Hellenistic. The wall foundations, which were part excavated in two sondages, provided pottery from (7590) and (7594) that will help date the earliest phase of construction. Pottery was retrieved from infill (8750) overlying the plaster surface in Space 217, and from topsoil excavated below the wall collapse (8730), so the date of abandonment may also be verifiable. The structure stood in a prominent position, albeit below the East Mound summit, and warrants further investigation and analysis over future seasons.

Post Neolithic wall foundations were identified immediately south of Building 41 and may well be contemporary with it. Further post-Neolithic walls were also revealed towards the southern limit of 4040. None of these features were excavated, and so also await further investigation over following seasons.

Burials

Approximately 22 Classical, Byzantine/Roman or Hellenistic period burials were excavated in the 4040 area this season. As with the Neolithic burials, the later period skeletons were only been excavated where they were disturbed during topsoil removal. Some of these late skeletons had grave goods, mostly consisting of complete ceramic vessels. Occasionally the burials contained more delicate items such as beads, and in one case a gold earring. In addition to the excavated skeletons, a number of late burial cuts have also been identified, drawn and annotated on the overall 4040 plan. These burials were not excavated in the 2003 season; which will be carried out in forthcoming seasons.

Space 100 - Ulrike Krotscheck

Introduction

The Stanford University field school at Çatalhöyük is projected as a five-year project, commencing in the 2003 season and continuing through 2007. The first season of the Stanford project was spent mostly clearing the 4040 area and mapping it with the intent of finding a roughly contemporaneous community of buildings on the site. After three weeks of scraping topsoil and mapping, the Stanford team was the first to embark on the excavation of one of the houses exposed by the surface scraping. We cannot tell with any certainty to which Neolithic level this house – Space 100 – belongs. The results of the week-long excavation, following three weeks of surface scraping, were as follows:

Space 100 is located a few meters south of the BACH Area (Fig 17). Its walls abut those of other buildings on all sides. During the scraping of the 4040, double walls could be seen on all sides of the room. The relationship to these other buildings is still unclear. Space 100 measures approximately 5m x 5m, oriented slightly off the N-S axis, i.e. NNE-SSW. The northwest corner of Space 100 is indented, forming an extra corner which cuts approximately one meter into the room on both sides. As is common in the Neolithic buildings at Çatalhöyük, the walls are not exactly at right angles. The inside faces of the walls are dressed in several layers of plaster. Fragments of plaster were also found even in the topmost layers of fill in the room.

Figure 17: Space 100 in the foreground

In 2003, we did not get through more than ten centimetres of fill in Space 100, partially due to the fact that the Stanford team could not begin excavation until the last week of the season. Another hurdle was the discovery of one late inhumation cut into the west wall of Space 100 (7907). The burial was oriented W-E (cranium at the west end). This was clearly not a Neolithic burial, having been cut through two Neolithic walls. The closest chronological association we could conclude was ‘Late Roman /Early Byzantine’. Since the material remains of late antiquity are so poorly studied in the Çatalhöyük area, the absolute date remains unclear; anywhere between the 2nd to the 4th century AD is possible.

Skeleton 7907

The inhumation was poorly preserved, a rodent having eaten its way lengthwise through it (as can be seen from the rodent burrow), depositing some of the ribs and vertebrae to the west and north of the cranium. The head was apparently originally in a flexed position resting against the west, short end of the wooden coffin, of which fragments of mineralized wood and rusted nails still remain. The unfused pelvis, sacrum, and epiphyses of the long bones indicate that this individual was not yet out of adolescence. A molar still in the crypt confirmed this picture. While it is not possible to determine the gender of so young a skeleton in such a poor condition, the grave goods indicate it was a female. ‘She’ was extended, as mentioned, the cranium and part of the mandible found on the right scapula. The limbs were extended, both hands having rested on the hips, possibly grasping two burnt clay vessels (Fig. 18).

Figure 18: In situ grave goods

Grave Goods

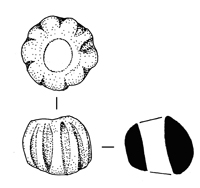

As poorly preserved as the skeleton was, as nicely preserved were the grave goods (Fig. 19). These included five so-called ‘melon beads’ next to the right ankle, and two long ceramic vessels found adjacent to the femurs. These vases may have originally been placed in her hands. The elongated, narrow shape of these vases is common among Roman / Byzantine burials on the mound. Between the tarsals was a complete, small glass vessel, probably used for perfume. Most remarkably, however, was the discovery of one gold earring resting under the cranium.

Ceramic vessel 7906.X7 |

|

Ceramic vessel 7906.X8 |

|

Glass vessel 7906.X2 |

|

Gold earring 7906.X6  |

|

Figure 19: Grave goods with skeleton (7907)

2004 Season

For the next season, we anticipate at least one more late Roman/Byzantine burial, the cut of which is already evident in the northeast corner of Space 100. Further, we hope to continue to excavate the space, and ultimately, as other spaces in the surrounding area are excavated, we hope to be able to understand Space 100 within its contemporary context.

Acknowledgements

The excavation was directed by Shahina Farid, and supervised by Jo Lyon and Jez Taylor. The total number of people who worked on the 4040 area during July and August was 29. Staff were split into excavation teams, the composition of which altered regularly throughout the season. Teams and their members are listed below.

UK team: Pia Andersson, Raksha Dave, Bleda During, Gudmunder Jonsson, Sophie Lamb, Jo Lyon, Jon Sygrave, Jez Taylor, Emma Twigger, Lisa Yeomans.

Stanford University Field School: Reed Adam, Dan Contreras, Cassandra Cueller, Ulrike Krotscheck, Nathanial Van Vallkenburgh (Parker).

Turkish team: Serdar Cengiz, Eda Cizioglu, Guner Coskunsu, Vahit Dursun, Gunes Duru, Huseyin Kamalak, Asli Kutsal, Ali Turkcan, Selcen Yalçin, Mehmet Yürük, Candemir Zoroglu.

On site osteological work was carried out by human bone specialists Meral Atasagun, Basak Boz and Lori Hager. On site survey work and digitising of plans was carried by Daniel Waterfall.