ÇATALHÖYÜK 2004 ARCHIVE REPORT

| |

RESEARCH PROJECTS

The Children of Neolithic Çatalhöyük:

Burial Symbolism and Social Metaphor

Sharon Moses

Cornell University

Abstract

The burials of Çatalhöyük have received a great deal of attention since Mellaart first began excavations in the early 1960s. His initial publications regarding beneath-floor and platform burials have piqued interest in this Neolithic community, and raised questions surrounding their cosmological beliefs. Under the auspices of Ian Hodder and the Çatalhöyük Research Project, new methods, technologies, and archaeological perspectives have breathed new life into the interpretive process of the site, and subsequently invited a number of research projects. One of these projects is the focus of a Ph.D. dissertation through Cornell University. This project examines the differential mortuary treatment between children and adults and what influences children, their social roles, and individual agency may have had upon ritual, concepts of sacred space, and traditions regarding death.

Özet

1960'lardaki Mellaart kazılarından bu yana, Çatalhöyük gömüleri ilgi odağı haline gelmiştir. İlk yayınında adı geçen, tabanların altından ve platformlardan çıkarılan gömüler, Neolitik toplumla ilgili merak uyandırmış ve kozmolojik inanışları ile ilgili soruları gündeme getirmiştir. Ian Hodder başkanlığında yürütülen Çatalhöyük Araştırma Projesi, yeni metodları, kullanılan teknoloji ve yeni bir arkeolojik bakış açısı ile kazının yorumsal sürecine yeni bir hayat kazandırmış ve birçok araştırma projesine kapılarını açmıştır. Bu projelerden birisi de Cornell Üniversite'ndeki bir doktora tezidir. Bu proje, çocuklar ile yetişkinler arasındaki gömü adetlerindeki farklılıkları ve çocukların neden etkilendiklerini, toplumdaki rollerini, ve ritueldeki bireysel katılımı, kutsal alan kavramlarını, ve ölümle ilgili gelenekleri incelemektedir.

Figure 102: From the “Great Bull” mural excavated by Mellaart, on display in the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations in Ankara.

Background

My first visit to Çatalhöyük was in Summer 2001. At that time, mortuary practices were my primary interest, but finding my own niche was something of a challenge. By year two, it was thought I could take on the Late Roman/Byzantine burials encountered in the later occupation of the mounds, but by the end of the season the Project Director, Ian Hodder, had revisited my proposal for working on the Neolithic burials.

What rendered my project's approach unique, was a Native American perspective of sacred spaces inside the context of an everyday lifestyle, and the use of visual performance/art toward communicating and perpetuating tradition. In a reflexive vein, I am aware that my interpretations will be influenced by my own cultural background, but it is my hope that ultimately the interpretive process will benefit from this perspective.

In Summer 2003 my focus became defined on children. Like gender issues, children have historically been relegated to little more than footnotes in archaeological reconstruction of ancient communities. This attitude has been changing over the past decade or so, and I am encouraged by the growing tide of interest that children as a legitimate topic have generated.

Themes

To better define my approach toward interpretation, it is best to examine several themes I want to explore. Specifically: children - their agency in social life as well as in death toward influencing the creation of the sacred; power - as it may have been perceived by the people of Çatalhöyük and what this might say about their ideology and social structure; sacred space - how this was defined and linked the dead, the living and the environment; visual language and color – the way the natural environment and elements from it was experienced and recreated visually to communicate ideas both sacred and profane with simple objects, accentuating the multivocality of material culture. I will explain these themes in more detail:

Children as Metaphor

As children are central to my research at Çatalhöyük, this project aims to explore burials and symbolic meaning through that lens. This in turn, may help to illuminate children's place in Çatalhöyük society and perhaps, metaphorically, about Neolithic society at large. While their mortuary treatment may stand in contrast to the reality of children's lives, this too, would be a valuable insight to social conflicts and negotiation within Neolithic society as expressed through and by children.

Children were selected at a higher percentage rate than adults for mound burial. I hesitate to conclude that child burials are simply a reflection of infant mortality rates; to do so would reduce the practice to nothing more than “equal proportioning” of body placement and would be contradictory to the evidence that burials were imbued with specific ritual and meaning.

The manner of burial ritual taken in context with architectural and spatial uses in daily life at Çatalhöyük, suggests to me that children played an important role in the negotiation between the living and the dead and were integral to the perpetuation of tradition and identity for the houses. “Ancestor worship,” a phrase that has been applied to Çatalhöyük and other Neolithic communities, implies the role of elders, of those who lived full lives and created the path between the past and the present. While elders and established members of previous generations are integral to the concept of tradition, how then, does the role of children play in the negotiation of memory, identity and maintaining the past through lives cut short? I believe the answer lies in part, in the social constructs of membership; within Çatalhöyük's society as well as external to it. This project hopes to explore the agency with which children influenced views of death and perpetuation of tradition and in their value toward creating the sacred.

Infants and children appear to have had greater flexibility in burial placement at Çatalhöyük than adults, who seem to have a more rigid guideline and a preponderance of burial in “clean” areas (Hodder and Cessford 2004). Infants and neonates can be found in clean areas as well as near hearths and ovens. In one instance, an elderly adult female was buried beneath a southern platform adjacent to the hearth area of the house (5169) in Building 17, Level IX. The clay ball found at her feet seems to suggest a material connection to the oven. Even though she is technically not buried next to the oven, she is one of the few adults that comes this close while maintaining burial in a recognized traditional adult space.

As has been established, the south side of the house where roof entrance coincides with ventilation for cooking has been typically designated “dirty” because of higher traffic and activity levels. I hesitate to use the term “dirty” area in discussion of burials, however, as it might seem a priori to minimize the importance of burials found in these zones. However, I would submit that children's burials are perhaps guided by symbolic meaning for the house quite distinct from those applied to adult burials but no less significant.

Child burials are more often accompanied with grave goods than adults. This project's research includes examining types of grave goods, incidence, and color while looking for multivocal significance to both sacred and profane worlds.

Thus, children can be seen as a metaphor for other social values at work within that community. That is not to suggest that children held elevated positions simply because ritual/religious symbolism utilized them. History of religion illustrates that even though women, for example, may have iconographic status, mythological importance, or inclusion in a pantheon of deities, this did not translate into higher status for human women in everyday life. Their representations were often used to negotiate or control a status quo or an ideal , as often as not to the detriment of their human counterparts (Pollock&Bernbeck 2000). I would posit that at Çatalhöyük children and their burials were also used in ongoing conflict and negotiation of tradition.

Power

It has been demonstrated that the burials to population ratio of the mound do not match (Hodder and Cessford 2004). Clearly, much of the population was not interred beneath the houses on the mound. Thus, without the data to indicate what percentage were subject to mortuary practices off the mound and what form those mortuary practices may have taken, it is at this time, unproductive to attempt applying our understanding of those “special” mound interments as though they are typical indicators of the general population. Rather, they are indicators of specific and purposeful acts of ritual, differentiated from those off the mound, and meant to communicate to the spirit world and to the living community, a meaning which must indeed have been perceived to hold a great deal of power.

Power and the dead will be a reoccurring theme in my interpretations. “Power” can assume different forms, particularly from the perspective of daily life in a pre-literate society's world view. Rather than a conscious separation of sacred and profane, often the two overlap and supernatural elements and multiple meanings are embraced in the course of everyday behaviors.

As an abstract form, “power” can be translated as tradition, legitimacy, and authority. As a material form, it can be a passive and an aggressive agent, an entity in its own right. As a source of beneficence as well as potential danger, power is a force to be dealt with properly, and only by those with specific knowledge. Depending upon the context of expression, visualizing a ritual and its implied power can help to illustrate: 1) what a community defined as power, 2) the kinds of value they placed upon it, and 3) how they perceived their relationship to the physical as well as the non-physical world through its agency. While it is impossible to place one self in the minds of prehistoric people, I believe it is possible to reconstruct the elements of ritual and symbolism established by the evidence of performance, to better grasp the mind set .

Subadults account for approximately 57% of the burials at Çatalhöyük compared to 43% adult burials. As we do not know the overall mortality rate of the mound, we can only say this demonstrates a preference for child placement there, but not how this corresponds to infant mortality.

Figure 103: Based upon 163 individuals as identified from primary, secondary and multiple grave pits.

Flexibility of children's burials has been interpreted by some as an indication that children held little power in society and therefore burial placement was not as ritually crucial. However, ethnographic and historic examples such as in the Native Americas, illustrate that a death of a child was thought to release special power, and that in some cases children were considered closer to the gods. Their bodies were used as vessels of communication to the supernatural world and to bestow the power of blessing upon the living and future endeavors.

There are indications of what appear to be special ritual placement of neonates at Çatalhöyük, which can be differentiated from general child burial. These appear to be foundation deposits for specific application to a “new” endeavor; the construction of a new structure or change in the use of space.

There were three neonate interments ((2515), (2199), and (2197)) at the threshold between two internal rooms of Space 71, Building 1 (subphase B1.1B; North Area) and one neonate (2532) with an adult female (2527) in the fill (a likely mother and child pair). The four neonates were buried during the construction phase of Building 1, but it is notable that neonates are thereafter absent from the general burial rituals that occurred in the lifetime of that building (Cessford in press). In contrast to a section of the South Area (Bldg. 6, - VIII & Bldg.17 – IX specifically) which shows a preponderance of infant burials that account for two thirds of the burial sample in those buildings. This area correlates to what was once designated as Mellaart's Shrine 10, Levels VI.A, VI.B, VII and VIII in previous excavations, and where elaborate wall art was found.

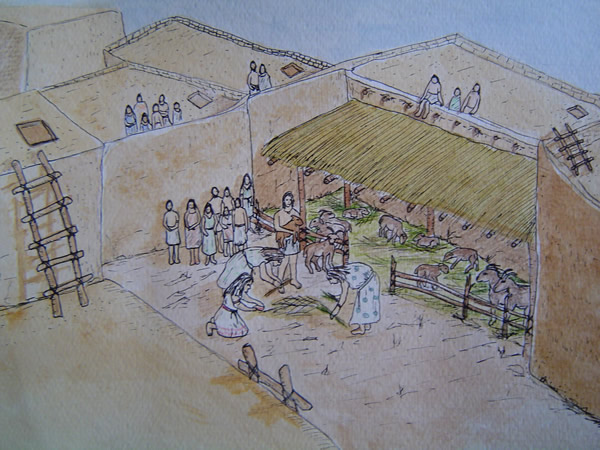

A neonate burial was found in Space 199, feature F.525, South Area. The neonate was in a basket and placed in a shallow grave in an open area, approximately five meters east of a wall (F.551). Its extramural status identifies it as unusual. Because the burial occurred in the transition phase to Level XII, and also marked a change in the use of the space from a midden to a penning area, the context seems to suggest that the burial served as a foundation deposit. Ritual burning activity appears to have taken place directly adjacent to this burial, sealing it. This would establish a link between the power of a child burial in relation to creating a sacred public event, and in this case related to animal care.

Figure 104: Ritual burning in proximity of extramural child burial, marking transition of midden to penning use of space in transition to level XII. Illustration by S. Moses

Infant burials can also be found in hearth and oven areas at the south end of the houses. Scoops and caches of obsidian, clay balls and other household items have also been found there. Beyond assuming these items were stored in rooms for processing activities, it may be helpful to consider other meanings associated with the proximity of child burials. Although less obviously ritualistic than the two examples previously cited, child burials in the hearth areas may also have been used to release power and beneficence upon items that were central to the functioning of the house.

I would posit that child burial could have been symbolic of a specific kind of power at Çatalhöyük and that this was used to benefit the house, the community and linked wild and domesticated symbolically. This project hopes to further illuminate these links.

Sacred Space

The natural environment juxtaposed against the created environment of Çatalhöyük, has much to offer in the interpretation of ritual meaning and sacred spaces there.

The beginning of intramural burial and/or burial in adjoining living spaces is believed to have begun in the Near East and likely in areas where domestication of plants originated (Kuijt 2000). Intramural burial and burials in otherwise “secular” areas have occurred primarily in communities where early farming and seasonal changes played a significant role in lifestyle (Pearson 1999, Kuijt 2000).

Despite the implication posited for the origins of intramural burial, i.e. that placement of the dead had a direct correlation with seasons and domestication, and resulting need to claim spaces amidst a growing population - my project is focused on the alternative approach of exploring ways in which the landscape was imported symbolically for religious reasons into the artificial/created spaces. Child burials may have provided a liminal link between the sacred and the profane, and in its creation and maintenance.

Continuing with the example above, southern orientation for external access as well for placement of hearths and ovens (thought associated with the roof opening for ventilation) can be interpreted beyond functional uses. This southern zone has been termed a “dirty” area, and most likely a profane area, based primarily upon material evidence of higher traffic and posited activity levels. However, based upon symbolic evidence, the southern entrance could also be representative of the very sacred.

Southern orientation, clearly one of the traditions and conventions observed for centuries and successive generations on the mound, seems to suggest that “south” was a direction which held special meaning for the inhabitants. In some Native American communities, house entrances and orientation were consistently facing east – where the sun arose each day and symbolic of the realm of the Creator god and/or origin myths, from where “the People” arrived into the world as does the sun each day. East is most holy of the directions in those communities, and the entrance of the house was symbolically acknowledging this as an integral part of tradition. Ritual performances utilizing the entrance of the house were charged with power issues, crossing the threshold was imbued with many taboos and specific to whom could enter.

There is no specifically functional reason why the residents of Çatalhöyük had to build their houses with southern orientation. I would posit the reason was not functional, but spiritual, and that the burials and other items within the southern rooms could also benefit from this consideration in the interpretive process. In the course of this dissertation project, I hope to further illuminate alternative ways spaces and burials may have communicated meaning.

Visual Language, Color, & Multivocality of Material Culture

As in any pre-literate society, visual and oral communications are vital to the perpetuation of tradition, skills and knowledge. Much has been written about the manner of transmitting and processing information in societies in lieu of the written word (Basso 1996; Goody 2000). The landscape and everyday resources are imbued with multivocality, speaking to secular needs as well as functioning as props and symbols of a sacred world.

Performances, and invitation or availability to see the performance manages who will have access to the information. Hidden knowledge is particularly key to membership questions – memberships in clans, house societies, and other social groups within a community. In this context, this research project is aimed at offering additional insights by looking at the manipulation of children's burials toward maintenance and perpetuation of tradition. Tradition is, despite its inflexible moniker, under a constant state of negotiation and challenge. Children and their status in death were integral to the communication of the sacred and tradition at Çatalhöyük.

In conjunction with performance and visual communication methods, I am exploring ways in which colors of environment were recreated in material culture, and ways this played a part in ritual language.

Much of the wall art of Çatalhöyük seems reminiscent of American southwestern sand paintings, which in Native American communities, are created for ritual and healing ceremonies, and then destroyed to release its power. Never meant to be kept indefinitely for aesthetic purposes, some of the wall art at Çatalhöyük was treated similarly, having been plastered over shortly after its creation (Last 1998). Beyond the obvious ritual art, I hope to illustrate ways in which everyday objects were multivocal, expressing both sacred and profane as context-specific, as part of the fluid nature of the sacred found in everyday life at Çatalhöyük.

Methodology

My research of Çatalhöyük is theory and thematically driven and employs an integration of data from different sources to reconstruct a bigger picture; a truly interdisciplinary attempt. Specialists' reports, ethnographic and historic sources and consideration and examination of material goods associated with burials and household life (which may also have served in burial ritual) will be included in the methodology of piecing together an interpretive picture of children in the religious life of Çatalhöyük. Despite the limited data base for Neolithic mortuary practices in general, I hope to incorporate examples of other Neolithic child mortuary practices from the Mediterranean and Near Eastern region and their associated ritual and symbolism in order to help put Çatalhöyük in context.

It is not my intention to define specific social patterns at Çatalhöyük, and then apply them to all Neolithic sites. I do however, believe there are general themes that can be detected but expressed in different ways among Neolithic populations – as undoubtedly people had interaction with one another and communities and individuals shared ideas and experimented with them or adapted them. Just as in Native North American communities, there are “themes” consistent with general Native cosmological views, identity and tradition, but which vary extensively from one region of the United States to the other, and from tribe to tribe.

While this dissertation project focuses upon children in Neolithic mortuary practices, I am thankful to Ian Hodder, Project Director, for offering me the opportunity to continue work on this topic, expanded to include adult burials and their symbolic nature at Çatalhöyük, in light of future excavations and publication.

| |

© Çatalhöyük Research Project and individual authors, 2004