Excavation in the South Area

by Shahina FaridThis year a six-month excavation season took place in the South Area, formerly called the Mellaart Area. The aim was to reach the base of the East mound to assess the effects of the falling water table across the Konya plain on the lower deposits at the site. When James Mellaart excavated in the early 1960's he hit the water table in a ‘deep sounding' where he excavated to learn about the origins of the settlement. Since then the potential of waterlogged deposits and preservation of organic remains of this period has been of great interest for research into the Neolithic environment. A matter of great concern has been that the falling watertable is resulting in dehydration and decay of any organic remains within the waterlogged deposits. A rescue bid is under way to control the water table below the site by reintroducing water to an appropriate height or maintaining it at its present level. Before this can be designed an evaluation was required to assess the damage already caused and to inform the best course of future action.

A core team of 20 was based at Çatalhöyük from April to October conducting the excavation and analysis. They were all joined at various stages by other team members for specific aspects of the project. The season was a great success, both in terms of achieving the aims of the project and on a social basis, this was due to the huge effort put in by everyone involved. The excavation took place over an alignment of buildings previously excavated by Mellaart which he called Shrines 1, 8 and 10. Renewed excavations took place below the levels that he reached where earlier structures attributable to Levels XII to VIB and pre-Level XII deposits were excavated and recorded. |

Figure 6: Hoisting material out of the deep sounding |

The watertable was hit immediately above natural marl, which was the base of the lake bed in the early Holocene. The surface of the marl was irregular, and the absence of any overlying backswamp deposits suggested it had been quarried in the Neolithic period.

The area then appeared to have been used as an off-site waste ground for the settlement which probably lay to the east of the current excavation area. The deposits were large banded ‘dumps' rich with cultural debris of largely animal bone, with charred plant remains, obsidian, stone, some shell and fired clay objects. The deposits had been reworked by alluvial activity from the ancient river that ran along the western edge of the settlement.

The area continued in use as a ‘waste' ground but the nature of the deposits changed to fine layers and lenses accumulated over time which had not been alluvially reworked but contained the same range of artefacts. The change of deposition may be attributable to a phase of construction beyond the area under excavation as the deposits were characteristic of ‘midden' found bounded by standing buildings excavated elsewhere on the site. Evidence of lime working was found within the sequence of ‘midden' as well as two phases of shallow gullies.

The area was then developed by the construction of a building attributable to Level XII. This was represented in the area of excavation by one wall only, the main body of the building lying beyond the trench to the west. The associated phase excavated was interpreted as ‘stable' deposits for penning animals, an infant burial and a small hearth were also found. The succeeding Level XI wall was constructed over the Level XII wall and the area continued in use as a ‘stabling' area.

In Level X the ‘stable area' was redeveloped, Buildings 23 and 18 were constructed, which in Mellaart's terms were called Shrines 1 and 8 respectively. These had been partially excavated by Mellaart in the 1960's and it was through Building 18 (Shrine 8), that Mellaart had excavated his deep sounding. The plan of the succeeding buildings that were recorded this season showed little change from Level X through to Level VII. The most noteworthy difference being that both in Levels X and IX the buildings shared party walls with connecting access holes. By Level VIII and later each structure had its own set of four walls resulting in double walls, probably the result of independently constructed buildings rather than construction of ‘neighbourhoods'.

Figure 7: Level VIII buildings (click for larger image) |

Figure 8: Level IX buildings (click for larger image) |

Figure 9: Level X buildings (click for larger image) |

Both Building 23 and 18 shared the same ground plan, with narrow rooms to the north and larger rooms to the south. The narrow rooms housed a series of plaster bins and were probably used as ‘storage' areas. The larger rooms to the south housed multiple phases of oven and hearths concentrated to the south and contained by shallow ridges separating the ‘dirty' ashy deposits associated with the fire installations from the ‘clean' plaster floors. With each successive oven or hearth rebuild the location moved slightly but always restricted to the southern area. Most of the large room of Building 18 had been excavated by Mellaart but the deposits that survived in Building 23 showed the ‘clean' floors were multiple applications of plaster, two infant burials in baskets cut these floors during the life span of the building. To the west was a further division of the room by a raised ‘step' which defined an area of plaster basins and possibly modelled posts.

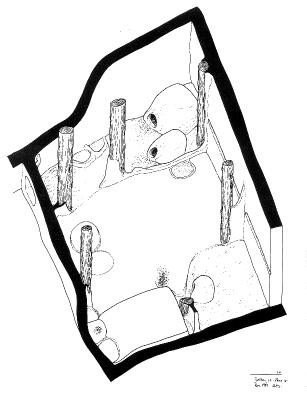

Figure 11: Reconstruction drawing of building 17, phase III |

To the east in what was called Shrine 10, Level IX, Building 17, was excavated. This consisted of two rooms, a narrow room to the west and a larger one to the east connected by an accesshole in the north corner of the party wall (Figure 11). The building was not completed this season however three internal modelling phases were identified. The use of the narrow room was unclear, the deposits contained accumulated occupation debris strewn with animal bone, pottery sherds and obsidian. The larger room showed more organisation with defined ‘dirty' areas for the fire installations and ‘clean' areas of successive plastered floors. A series of ovens were housed in the northeast corner, basins in the southwest, a hearth area in the southeast, and a platform against the south wall. The hearth and the platform in the southeast corner and along the south wall remained until the final phase. However, the ovens in the northeast corner were sealed and raised, over this a series of basins and bins were constructed, whilst the oven was moved to the southwest corner and an additional platform constructed along the western wall. Two infant burials in baskets cut the floors along the eastern wall and an adult burial cut the southern platform. |

The overlying Building 6, of Level VIII, was mostly excavated by Mellaart, but survival of some of the archaeology reflected a similar pattern of features moving across the room at different phases of use. The ovens moved from the northeast corner to the centre of the south wall, a platform was located in the southwest corner and remnants of plastered basins and modelled posts were located along the northern wall. Nine individual burials were excavated, three adults and six infants. One of the adult burials was headless (Figure 12) and a second was buried with a concentration of owl pellets across its torso. The infants were mostly buried in baskets and one was intact enough to lift as a block and is currently on display in the Konya Archaeological Museum (Figure 25). This infant was ‘adorned' with stone and bone bead bracelets and peardrop-shaped bone bead anklets. |

Figure 12: Burial 492, building 6 |

The narrow room had a different function at this level, it housed a hearth to the south, and plaster bins to the north. An infant burial was found close to the hearth. Remnants of Levels VII and VIB buildings overlying this narrow room were also excavated.

During the course of the excavation peripheral work was conducted to reduce the hazardous heights of surrounding walls. Also, Building 2 of Level IX, largely excavated last year was completed. The excavation of its wall plaster revealed a small area of painting in the northeast corner. This was red ochre on white plaster, which formed a pattern of concentric lozenge shapes (Figure 26). Overlying the red paint were traces of black painted lines but these were too discontinuous to form an image. The painting is also currently on display in the Konya Archaeological Museum.

A regular pattern of the internal organisation of the buildings at Çatalhöyük is emerging showing defined areas of activity for specific functions. As more complete buildings are excavated our understanding of individual buildings as ‘homes' for individual families is being challenged. It is not unexpected that the majority of buildings seem to follow the same general layout and internal furnishing requirements, each building required a ‘cooker', a ‘bed', a ‘rubbish bin' etc., as much then as we do today. A variation in the number of burials per building and the total absence of burials in some buildings, must be questioned. This could be interpreted as the existence of focal buildings for extended families. When Mellaart defined buildings as ‘Houses' or ‘Shrines', he based his interpretation on the internal furnishing, ‘artwork', ‘ritual' content and the number of burials. Shrines were defined as the ‘priestly' quarters but perhaps they were the ‘focal' house of related or connected individuals or groups.

Further work also needs to be done on the significance of the movement of the internal features within a building, specifically the ovens and hearths. Generally fire installations were located to the south of the building and concurred with the location of ladder emplacements (when found) for access to the roof, and as such, the roof access also functioned as chimneys. Did the movement of the ovens therefore relate more to the activities that took place on the roof or was it connected to the general ventilation of the building?

From the limited area that has so far been investigated at the base of the mound it has not been possible to determine the manner in which the settlement grew at Çatalhöyük. If the very basal deposits represented off-settlement dumps it can be assumed that the focus of the settlement lay deeper into the mound to the east. Questions as to whether the buildings excavated so far developed from early ‘stand-alone' buildings remain unanswered. The pre-Level XII midden deposits may in fact have been bounded by buildings on all sides as in later levels, alternatively these may have been ‘stand-alone' buildings. That structural levels XIII and probably earlier existed is evident by the presence of pre-Level XII deposits.

However the goal to reach natural marl was achieved and the issue of the survival of waterlogged deposits at the site was addressed. Unfortunately, although the water table was reached, this was directly above marl and despite the lower deposits being damp there was no observable evidence of intact organic artefacts, non-charred structural elements or mass deposits of plant material, however that does not preclude the presence of environmental elements such as pollen, diatoms etc. The occasional artefact was recovered that suggested waterlogged material was present, for instance, a piece of wood interpreted as a discarded post, was found to have survived a number of environmental changes of partial carbonisation, apparent waterlogging and a period of desiccation.

The conclusion of the evaluation was strongly in favour of maintaining the water table at a constant level so as to avoid fluctuating environments within the archaeological resource detrimental to structural, artefactual and environmental remains.

Figure 10: Building 17 during excavation