ÇATALHÖYÜK 2003 ARCHIVE REPORT

| |

INTRODUCTION

Ian Hodder

This year the project celebrated its 10-year anniversary. Our work had begun in 1993, and the first major period of excavation by the Cambridge-Stanford team took place in 1995-99. The preparation of this work for publication has now been completed (4 volumes to be published by the BIAA and McDonald Institute). In the meanwhile other teams had also started digging – especially a team from the University of California at Berkeley (BACH – led by Ruth Tringham and Mira Stevanovic) and a team from Poznan in Poland (TP – Team Poznan led by Lech Czerniak and Arek Marciniak). On the West Chalcolithic Mound excavations were conducted under the leadership of Jonathan Last and Catriona Gibson (English Heritage and Wessex Archaeology, UK).

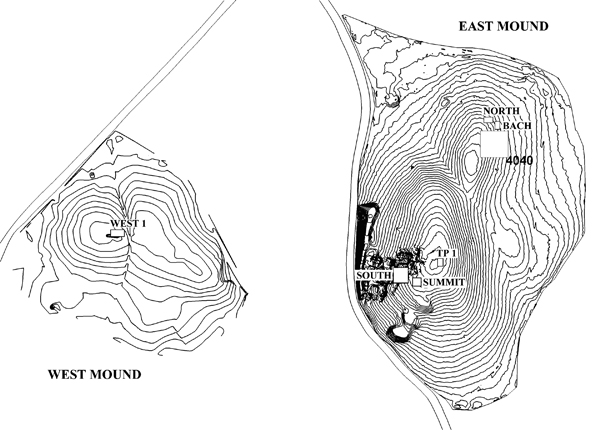

Due to unprecedented circumstances of war in Iraq plans for the 2003 season were curtailed and as such a smaller and shorter season was undertaken. Progress was made however, in our plans to open a 40 x 40 m area to the north of the East mound as well as to work under the newly constructed shelter over the South Area which also incorporates the Summit Area first excavated by a team from Thessaloniki (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Areas of excavation

Excavation

In returning to excavation after a break for publication, the main Cambridge-Stanford team decided to rather shift gears in terms of its aims in 2003. In our earlier work we had concentrated on individual houses. And the same was true of BACH and TP. We had all focused on the details of specific houses, how they were lived in, re-used and re-built and abandoned. It was time now to return to the bigger picture. Mellaart had excavated large areas in the 1960s, and we needed to return to this larger scale and work on how the site as a whole was organised. He and we had only found houses and areas of refuse. Were these buildings organised into groups? What was the social geography of the town? Were there bureaucratic or ceremonial centres that regulated the 3000 to 8000 people that lived there? How had the whole thing worked?

In order to examine these questions we decided to return to surface scraping as we had found in 1993-4 that the soil on the top of the mound was very thin. It only needed to be scraped with hoes for the walls of the latest buildings of the site to show up. In fact, by scraping large areas, the overall plan of part of the town could be recovered. So in 2003 we laid out an area 40m x 40m in size adjacent to an area in the northern part of the East Mound where we had previously already scraped and found the plan of about 40 houses.

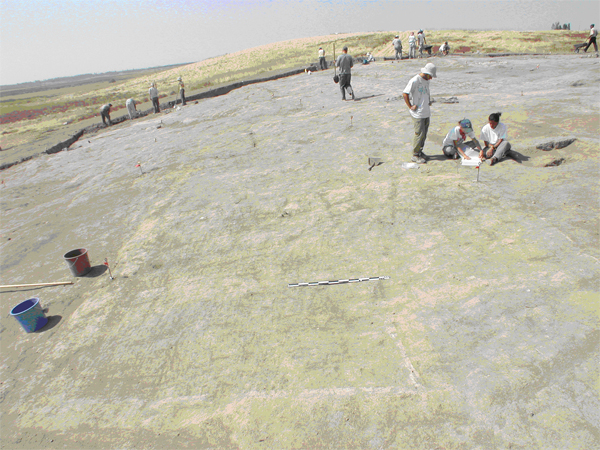

Figure 2: Uncovering Neolithic structures and late burials

We quickly started seeing the layout of more buildings. But we also came across various difficulties. For a start, the 4040 Area extended down the sides of the northern eminence (Fig. 2).But as soon as we got off the crown of the mound, the amount of soil that had to be removed increased, hoes had to be exchanged for heavier tools, and work slowed. Another difficulty was that we kept coming across burials. These were right at the surface of the mound and had been partly destroyed by erosion and soil slip. Their archaeological context was thus insecure. Nevertheless some rich Byzantine and Neolithic graves were discovered. A number of the Byzantine graves contained ceramic and glass vessels (see Fig. 18). But it was the Neolithic burials that were most surprising. One burial pit contained a large number of skeletons, one of which wore a copper armband and another had an alabaster one (see Fig.14). Other Neolithic burials contained stamp seals – the best preserved found so far by the current project. One of these was very remarkable. It looked like a leopard, but with its head broken off. Part of its tail was also missing but curving back to rest on top of the leopard (see Fig. 61).

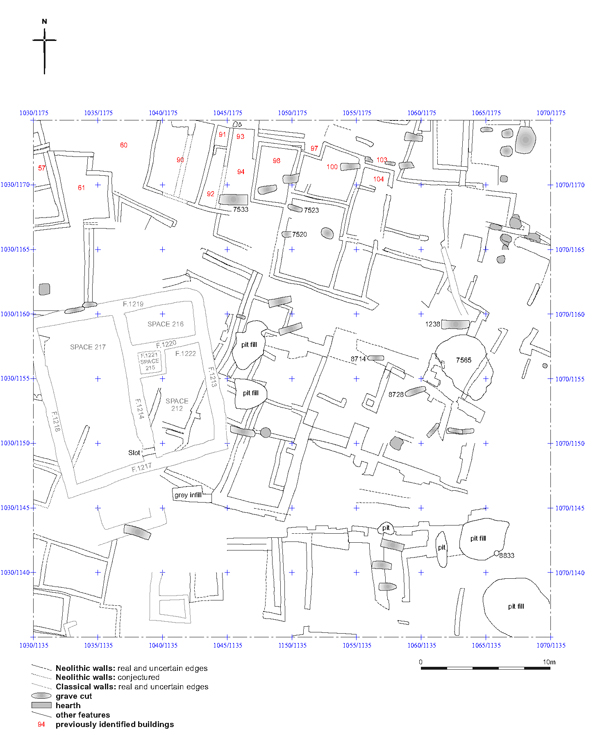

Right at the top of the northern area we found the foundations for a large building (Fig. 3). There was no dating material for this but we presume it is Hellenistic, Roman or Byzantine, and of uncertain function. Hopefully future excavation will find some dating evidence in the foundation trench. The overall plan of the Neolithic buildings, especially when linked up to the earlier scraped area was fascinating (See Fig.9). Definite ‘sectors’ could be identified. Houses were as usual tightly packed together, but there were gaps which defined clusters of houses (Fig. 4). In fact, these long linear gaps looked like ‘streets’ or ‘alleyways’. They seemed all directed towards the top of the mound. But instead of these alleys leading to public or ceremonial buildings, the top of the mound seemed to have been primarily used for refuse discard or midden. There were some buildings which seemed to have thicker walls, and we hope to excavate these in future years to see if in some way they are distinctive. But for the moment there is little evidence of public spaces or buildings – once again Neolithic Çatalhöyük seems to consist of just houses and midden. The pottery on the surface in the 4040 Area seemed to be mainly from about Level V, although material from other dates was also present.

Figure 3: Late Period-Building 41

Figure 4: 4040 Area showing all features identified

Excavations also started in the South Area of the mound. This is where Mellaart had excavated in the 1960s and we had continued excavating there in the 1990s. But each year the snows and rains had caused erosion and damage, and we had covered up our trenches each year to protect them. But over the last year we had constructed a huge shelter which could be completely closed in the winter. This was completed just before the digging season by Atölye Mimarlik. It covered 45m by 27m and created a wonderful even light and a protected environment for excavation, conservation and public display. We have already started putting back reconstructions of the art found by Mellaart so that visitors can understand the site better (Fig. 5). But we also started excavating beneath the shelter, continuing the excavation of Building 10 that had been started by a team from Thessaloniki. In this building we found a bench that may once have had horns inserted into its sides (See Fig. 39).

Other teams working at the site also continued their work. The BACH team completed the excavation of Building 3 by removing the walls and exploring the foundations. Behind the plaster on one of the walls they found an entrance that had been bricked up. This suggests that entrance into buildings at Çatalhöyük was not always through the roof – sometimes there was a door at ground level, at least in some phases of occupation of buildings (See Fig. 22). The TP excavations on the top of the main mound had been dealing for years with Byzantine burials and Roman features. Finally their patience was rewarded this year by a most remarkable find. After excavating through some very exiguous late Neolithic buildings, they came across what we think may be a wonderfully preserved collapsed roof! We had seen broken bits of roof in some earlier excavations – especially in Building 3. But this one seemed to be very well preserved (See Fig. 27). Lying at a sharp angle as a result of its fall, it consisted of thick layers of plaster interbedded with occupation deposits. Excavation of this next year will give an important and full picture of what activities took place on the roofs of the Çatalhöyük houses – at least in the warmer summer months.

Figure 5: South Area with reconstruction painting

Other activities

The project was honoured to host a visit by Nadir Avci, Director General of the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism and his assistant Ílhan Kaymaz (Fig. 6), for a formal opening of the South Area shelter. The event was also attended by local politicians from Çumra and Konya and covered by local and national press. The project was hailed as a positive contribution to the Konya region and much support was voiced for the work of the project in its international character and the number of visitors the site attracts.

We also played host to about 70 school children from Istanbul, Konya, Çumra and Küçükköy. A day long event with the children taking part in many on-site activities was organised by TEMPER (Fig. 7). TEMPER (Training, Education, Management and Prehistory in the Mediterranean) is a Mediterranean-wide heritage project that involves six partner institutions. Its aims over a two and half long period funded by the European Union is to raise awareness of the importance of the prehistoric heritage of the European Mediterranean and to encourage best practice in site management and produce educational programs to encourage school children and adults to visit the sites and to develop an interest in prehistory at national curriculum level.

Towards the end of the season our newly established Geomatics team organised the use of a portable Cyrax® 2500 3D Laser Scanner (Fig. 8). The scanning equipment was generously loaned by Cyra Technologies through their parent company Leica Geosystems and the professional geomatic experience was provided by Plowman Craven & Associates, UK, to whom we are very grateful. This equipment enabled us to record Neolithic buildings at Çatalhöyük in a way that has been impossible in the past. With this 3D technology our plans for the future is for a virtual Çatalhöyük building to be accessed on the web with spatial information. Towards this end we are radically updating our database into a truly relational environment and to provide a fully integrated, updated in real time, 'live' database linked to spatial and image data that is accessible to all of our team from any part of the globe regardless of operating systems.

Finally, as in previous years the Thames Water Scholarship to assist young Turkish archaeologists was awarded. The three successful candidates are: Nurcan Yalman with assistance towards her PhD at Istanbul University in Ethnoarchaeology which involves attending some lectures at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London. Gunes Duru also at Istanbul Universit and also to attend classes at the Institute of Archaeology, University College London and, Meral Atasagun from Selcuk University to attend an English language class in London to help her in her Masters studies.

Last years candidates successfully completed their chosen courses and will submit short reports on their research which will be posted on the project web site.

Acknowledgements

The project works under the auspices of the British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara, with a permit from the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism. The project is grateful to Nadir Avci and to our temsilci Belma Kulaçoglu.

Much support of the project is provided by politicians and officials in the local town of Çumra, especially the Belediye Baskani Zeki Türker and the Kaymakam Osman Taskan. Much gratitude is also due to Erdogan Erol, the Director of Konya Museums.

The main sponsors are Koçbank and Boeing. Our long term sponsor is Shell, and other sponsors are Thames Water and IBM. In Britain support has been provided by the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, and the British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara. In collaboration with the Museum of London Services we had field support from the Museum of London Archaeology Service and IT support from the Museum of London. Much research support is provided by a number of UK universities: the Institute of Archaeology, University College London, University of Cardiff, University of Sheffield and University of Nottingham. In America funding has been received from Stanford University, the National Science Foundation, including the Research Experience for Undergraduates programme, the U.C. Berkeley Archaeological Research Facility and MACTIA. Generous private donations have been made by John Coker. In Poland thanks are due to the University of Poznan, and the Polish Academy of Science. Other support is provided by the Friends of Çatalhöyük and the Turkish Friends of Çatalhöyük, and we are grateful as ever to Jimmy and Arlette Mellaart. Special thanks is extended to Ömer Koç for his continued support of the project.

Finally the team would like to thank and wish all the very best to Melih Pekperdahci, our devoted camp manager since 2001. We will miss him but hopefully this will not be goodbye as in the tradition of the camp managers job which was passed on to Melih from his brother Tolga, the job remains in the family and passes on to his cousin Levent Özer who will join us in 2004.

| |

© Çatalhöyük Research Project and individual authors, 2003