ÇATALHÖYÜK 2005 ARCHIVE REPORT

| |

STUDY SEASON REPORTS

Figurines

Lynn Meskell (University of Stanford)

Carolyn Nakamura (Columbia University)

Abstract

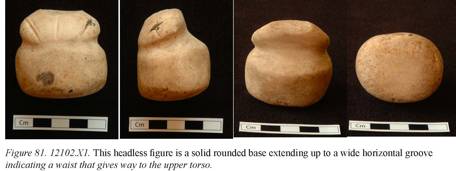

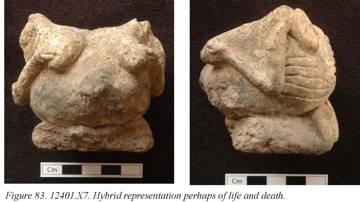

This year the figurine team focused on recording basic information for all of the 1526 objects in the miniature shaped object corpus. As a result we were able to perform some preliminary spatial analyses, which allowed us to begin discussing notions of process, context, and circulation of figurines at the site. In addition to finding more of the common abbreviated and zoomorphic types, excavators uncovered some less common and new forms. The 4040 and IST surface scrape uncovered two very small unsexed human clay figurines with protruding stomachs and buttocks (11324.X3, 11848.X1). Another anthropomorphic stone figurine was found in a midden in 4040 (12102.x1), similar to 10475.X2 from last season, but with the head and neck sawed off. Another midden unit, (10396), in the 4040 produced 11 figurines/fragments (most zoomorphic). Finally, the IST team found a very atypical human clay figurine (12401.X7) that depicts a robust female on the front and a skeleton on the back; the neck has a dowel hole and the head is missing.

Given the diversity of this collection, we seek to explore the various assemblages and materials as figured lifeworlds. A notion of figurine as process, rather than object or end product is therefore central to our project. Given their specific materiality (portable, three-dimensional, miniature), figurines can render multiple levels of representation and participate in, or even anchor, storytelling activities that mediate issues of memory and identity. We find the wider practices of embedding materials, and the circulation, plastering and defacement of body parts to be evocative gestures that intersect with many figurine practices. These may embody and express particular notions and relations of life and death cycles and we plan to explore these issues and connections more fully in future seasons and publications.

Özet

Bu sene figürin ekibi, 1526 adet ufak buluntunun basit verilerinin kaydı üzerinde yoğunlaştı. Bu çalışmanın sonucu olarak, Çatalhöyük’deki figürin dağılımı, kavramsal methodlar ve kontext gibi ilk analizlerin sonucu olan verileri tartışma imkanı bulduk. Genelde bulunan daha kısaltılmış, hayvana benzer örneklere ek olarak, bu sene daha farklı, yeni şekiller bulundu. 4040 ve İST alanlarındaki yüzey kazımaları sonucunda iki adet, çok küçük boyutta, seksi belli olmayan çıkık, göbekli ve kalçalı insan figürinleri bulundu (11324.X3, 11848.X1) . Geçen sene bulunan figürine benzeyen 10475.X2 ve 4040’daki bir çöplükde bulunan bir başka insan betimli taş figürinin başı ve boynu kırıktır. 4040 alanındaki diğer bir çöplükde, 10396, 11 adet figürin ve parçaları bulundu (Çoğu hayvan betimli). Ayrıca İST ekibi, ön tarafı kadın, arka tarafı iskelet olarak betimlenmiş, boyun kısmı delikli ve başı olmayan, olağan dışı bir kil figürin ortaya çıkarıldı.

Introduction

This year we continued to build up the database archive and refine the system implemented last year in 2004. Although much work remains to be done, we were able to compile basic data (material and form) for nearly all objects and fragments in the collection in terms of material and form, enabling us to perform some preliminary spatial analyses. The findings from these analyses now allow us to discuss notions of context and circulation of figurine materials at the site and thus address and challenge some popular conceptions about the Çatalhöyük figurines offered by Mellaart and others who have studied the materials previously. We aim to present a more comprehensive and representative range of figurines from the site, balancing out the sensationalized finds of the so-called ‘Mother Goddess’ images with the ubiquitous abbreviated figural and animal forms in clay. Our initial findings pose a challenge to the special status given to the category of figurine and its commonly assumed associations with art, women and religion. The diversity of the Çatalhöyük corpus alone demands that we examine a number of variables and interpretations beyond those specified, implicitly and explicitly, by the simple category of figurine.

An overarching goal of this research, then, seeks to make a decisive move away from the notion of figurine as thing; rather, we propose to view the figurine as process. As we emphasized last year,our database design process did not simply involve archiving the collection, but engaged a critical rethinking of analytical and interpretive categories oriented towards a more integrative approach to figurine studies. We suspect that certain types of figurines will find closer ties to wall art, representational architectural features, and to plastering activities in general than perhaps to other types of figurines. Refocusing figurine research towards such areas of overlap prompts a productive rethinking of our taxonomic framework in terms of processes of resource acquisition, technological and gendered production, and use rather than in terms of the end product. This approach broadly embraces the idea that technology is social before it is technical (Foucault), thus allowing us to consider the social processes involved material selection, preparation, fabrication, use, circulation and discard.

By developing these aims, the larger interpretative issues of self-representation — the negotiation of self and sexuality, and relations between human and animal worlds — might thus come into sharper analytical focus. We seek to move away from sterile attempts to deduce function and meaning from a visual reading — the ‘is it a deity or not’ type of equation? Instead we seek to look and maneuver around the objects, weaving together patterns of figurine making, technology, use, mobility and discard, coupled with the traversing of categories from figures to plastered features to wall paintings. In this way we hope to build up more of a lifeworld for the Neolithic community, taking into account the inherent visuality and materiality of a figured corpus.

Given our knowledge of representational spheres at Çatalhöyük, this prompts us to ask was there something special about settling down in tightly packed communities in the Neolithic that make its inhabitants more attentive to the contours of personhood and sexual identity, are they playing with classifications and categories that we might find unfamiliar? But first of all we have to balance the scales in terms of readily identifiable genders as the numbers of male, androgynous, phallic and ambiguously sexed figures needs to be recalculated. This is a task we have taken seriously over our first two seasons and are close to achieving a fuller picture of the entire range of material. A notion of becoming at this site might then have encompassed experimental imagery that incorporates various sexual symbolism, or combines innovative ways of viewing attributes depending on viewpoint, movement and circulation.

The following report will provide a brief discussion of the current status of our work, including the identification of some key issues, work completed, new finds, the presentation of some preliminary analyses and interpretive directions, and plans for future work.

Issues addressed and work completed

1.The Archive

At a fundamental level we need some dialogue between the two periods of excavation in terms of material culture — even if not the stated contexts, given the levels of specificity in recording during the 1960s (Todd 1976). The scale and speed of the early work uncovered a dazzling array of materials, yet lacked the benefit of the present project’s careful, contextual methodologies. This is evinced very clearly with the figurine corpus. If one were to take the Mellaart finds at face value, specifically the published pieces and thus ignore the wide variation in figurine types, then one might posit that two rather different sites had been dug (see Mellaart 1962; see 1964; 1965; 1966; 1967; 1975). Mellaart would have uncovered a large number of impressive stone and clay pieces, whereas conversely our project would have found more mundane clay examples of quadrupeds, bucrania, abbreviated human forms and so on. Though we have found impressive examples, the mundane dominates numerically. One way to challenge this picture is to re-excavate Mellaart, to literally work in his areas and through his spoil. A training and educational excavation (TEMPER) under the aegis of the wider project carried out the latter and we now have a very good idea of what Mellaart missed, overlooked or even discarded. Our numbers indicate that he missed significant numbers of figurines (anthropomorphic and zoomorphic) along with fragments of them, non-diagnostic pieces, shaped clay pieces and scrap that is probably ceramic debitage.

One of our first tasks then was to investigate whether this discrepancy largely can be explained away by differences in excavation methodologies and goals or whether it, in fact, does present some kind of meaningful patterning. Others have previously made assertions concerning figurine patterning at the site (Hamilton 1996, in press; Voigt 2000), however, we remain highly skeptical of such analyses given that they have assumed a certain equivalence between the 1960’s and current excavation collections and not taken differences in excavation methodologies into account. In order to make any meaningful comparisons, some attempt at balancing Mellaart’s picture must be undertaken. Fortunately, we were able to address this issue somewhat by including materials from Mellaart’s study (etutluk) collection (The project became aware of these materials last year when the Konya museum turned them over to the project to store on site after they were deaccessioned from the Ankara collection. To our knowledge these materials have not been studied previously), and materials found in his spoil heap dug by the TEMPER project (see archive reports 2000-2004). Materials from the current excavations in Mellaart’s area (now called the South Area) also contribute to balancing out the Mellaart profile. The emerging figurine database will include these materials recorded in appropriate detail. Given that contextual information is missing or mimimal for most of these materials, they cannot be used in analyses that look at patterning over time and space.

2. The Database

Initially, we designed an extensive database to accommodate a broad range of shaped objects to ensure that we did not overvalue the category of figurine. This decision has resulted in a database record of over 1500 objects, many of which are non-diagnostic fragments and scrap. After having become more familiar with the figurine materials we have decided to employ a tiered recording methodology. Although we have not yet worked out the specifics for this system, most likely it will involve fully recording all diagnostic figurines and figurine fragments, while recording only fabric and weight of the non-diagnostic pieces. Basic descriptive and contextual information for all objects will be recorded where possible. This season we accomplished entering this data for all objects present on site and all known objects from the Konya and Ankara museum collections. We focused on entering basic information that would allow us to perform some preliminary analyses of basic patterning across the site and over time:

ID number

Inventory number

Unit

Year

Area

Space

Building

Feature

Level

Location

Object Type

Material

Form (representational)

Type (representational).

These basic data also allowed us to investigate some of Naomi Hamilton’s assertions (2005), and conclusions from the heavy residue report in Volume 6 (see discussion below). As mentioned last year, we have structured the database in such a way that allows for the recording of objects from the most general, descriptive terms to more specific, interpretive categories. We believe that this provides the most flexibility for a variety of analyses. Given this consideration, we are eager to dispense with previous terminologies used by Mellaart and Hamilton such as humanoid, ex voto, schematic, mother goddess, fat lady, as they cannot be disassociated from problematic narratives from art and religion. Our process-focused approach challenges the idea of figurines as static, stationary objects to be viewed and kept in special areas. Hamilton herself presented alternative interpretations for some of the Çatalhöyük figurines, possibly as toys, or jewelry and adornment. While there is little evidence for such use, it is likely that figurines circulated throughout the site and we will put forth a few alternative possibilities.

3. Clay technologies

We continued to work with other clay material specialists, Mirjana Stevanović (building materials), Nurcan Yalman (pottery), and database specialist, Mia Ridge, to agree upon a common clay terminology that would enable better functionality of database queries. Although there are some basic commonalities between ceramics, figurines, building materials and clay balls, the fabric and firing technologies for each are quite specialized and substantially different. A broad aim of the project seeks to better understand the range of clay technologies employed at the site. The clay figurine fabrics are not uniform, although they do appear to cluster into a few different type groups ranging from coarse ‘dirty’ clay to very fine clean marl and plaster. Some fabrics do appear to be similar to miniature clay balls (see reports by Atalay) and possibly some ceramic fabrics (Yalman, pers. comm.) Next season, we plan to begin working out a methodology for the systematic recording fabric type and degree of heat exposure. Given that figurines are predominantly found in secondary contexts such as midden and fill, such work and the eventual comparison of fabrics across object types, will be important for getting at aspects of figurine production and fabrication, even if only obliquely.

4. Experimental Methods

Video and Multiple Perspectives. Given our interest in exploring embodied processes of crafting, decision making, material agency, and circulation involved in figurine practice (see 2004 Archive Report), we continued to document some of the figurines on video in order emphasize the experience of these three-dimensional, portable objects as likely viewed from multiple perspectives. The theme of ambiguity, both in terms of form and sex, needs to be addressed within the Çatal figurine assemblage. As we reported last year, most of the figurines are unsexed and often cannot not be assigned to any clear cut traditional category of male or female. This kind of ambiguity often exploits the three-dimensionality of a figurine, a form that can support multi-leveled and hybrid representations like the anthropomorphic and phallomorphic forms in Fig. 80. This specific materiality of a figurine also invites one to handle and manipulate it and view it from different perspectives. Given this capacity, figurines might likely have been engaged in interactive activities such as storytelling, wish fulfillment, didactic devices concerning transformation, and/or exploration of personhood and sexuality. Again, it is important to entertain the possibility that figurines operated outside of cultic and religious contexts, that it was not necessarily the object itself that was meaningful but the social activities their materiality anchored and supported.

Replications. We also brought some clay modeling material to experiment with re-creating some of the most ubiquitous forms found at Çatalhöyük (We acknowledge that there are differences between working with clay and working with oven-bake clay modeling paste, but given the sensitive issue of forgeries, we decided to use a modern modeling compound. All copies were destroyed after the experiment). We all encountered various levels of difficulty in this task (Participants included ourselves, John Swogger, Mira Stevanovic and Marina Lizzaralde). We imagined that the simplest abbreviated forms would take only five or six moves to make. But we found that despite their apparent simplicity, the zoomorphic and abbreviated figurines are of a particular cultural style (although there is no standardization of form, there is a certain level of stylistic consistency visible within the various types). The forms were surprisingly foreign to us even though we were constantly handling and examining them. At the outset, even the most experienced person (John Swogger) took some 15 moves to make an abbreviated form but with practice quickly paired the process down to 6 moves. For the animal figurines, fashioning the entire head and body from a single piece of clay proved to be difficult for us, but could be done with a certain amount of practice.

Fingerprints. After reviewing the literature on fingerprint analyses on ancient materials, we decided that correlating fingerprint ridge breadth with height and age would provide the most fruitful avenue for such research (Kamp, et al. 1999). Determining any statistically significant differences in ridge breadth due to sex requires a “genetically close” sample group for comparison (Cummins 1941; Jantz and Parham 1978; Malvalwala, et al. 1990; Stinson 2002). We find do not believe that any modern population can provide such a sample and find studies that assume genetic proximity based only on geographic proximity problematic. Although counts of figurines with fingerprint impressions have not been finalized, we took a sample of 34 print impressions from horn, quadruped, abbreviated and non-diagnostic forms. To avoid leaving a residue from the vinyl polysiloxane dental compound (Patterson Dental Supplies) on the figurine surface, we took impressions of the fingerprints using modeling clay and then lifted the print images from the modeling clay. In future seasons we plan to collect prints from all field samples that have such impressions as well as obtain permission to life images from the figures in the Konya Archaeological Museum.

2005 Finds

This year the project recovered 47 objects from excavation and 26 figurines from Mellaart’s spoil heap. Basic counts for the excavation finds are presented in Tables 1a-1c below.

Object Form |

Count |

|

|||

figural |

32 |

|

|||

figural, non-diagnostic |

9 |

|

|||

geometric |

3 |

|

|||

geometric, non-diagnostic |

1 |

|

|||

non-diagnostic |

2 |

|

|||

TOTAL |

47 |

|

|||

|

|

|

|||

Table 1a. 2005 Shape Objects |

|

||||

Figural objects |

total |

non-diagnostic |

Secure |

||||

anthopomorphic |

14 |

2 |

12 |

||||

zoomorphic |

19 |

5 |

14 |

||||

indeterminate |

17 |

9 |

8 |

||||

|

|

|

|

||||

Table 1b. Form Distribution of 2005 Figural Shaped Objects |

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

||||

FORM |

Total |

Indeterminate |

Secure |

|||

abbreviated |

4 |

4 |

0 |

|||

human |

6 |

0 |

6 |

|||

horns |

9 |

2 |

7 |

|||

quadrupeds |

6 |

3 |

3 |

|||

|

|

|

|

|||

Table 1c. Type Distribution of 2005 Figural Shaped Objects |

|

|||||

12102.X1

Description. The figure comprises a solid rounded base extending up to a wide horizontal groove indicating a waist that gives way to the upper torso (Fig. 81). Two diagonal (shoulder to waist), deeply incised lines indicate arms and a single vertical line divides the chest down the center and may be suggestive of breasts. The neck and head are missing, but have been cut off, probably with obsidian and other stone tools, and perhaps even polished after removal (Karen Wright and Adnan Baysal, pers. comm.).

Context. This figurine derives from a midden context in the 4040.

Discussion. Although the neck and head are missing, it is likely that this piece is similar to the example found last year in space 227 (10475.X2). Another example of a removed limestone head occurs with a figurine now in Ankara (79-8-65). Although speculative at this juncture, the removal of heads is a provocative theme for discussion. Such practices occur in human burials, and we have seen the circulation of heads after death repeatedly at Çatalhöyük. Within the clay figurine assemblage there are several headless bodies that have dowel holes in the neck and also small spherical objects that resemble heads. Certainly, there is the technological consideration that forming the head and body separately is easier for those less skilled in figure modeling. We found this to be the case in our experimental work with fashioning figurines. But given the presence of dowel holes (which allows the easy removal and exchange of heads) and evidence for the intentional removal of heads across the site, we suggest that figurines might be involved in activities of myth and storytelling. Figurine worlds may have provided a rich vehicle to explore narrative and transformative experience — the exploits of individuals, encounters with animals, mythic or historic. The ability for figurines to be malleable, to change identities through the transfer of heads (or change of viewing angle), presents an interesting set of possibilities and leads us away from static forms into the notion of figurine as process (see discussion below).

11324.X3

Dimenisions (H.xW.xTh.):2.84 x 1.41 x 1.14cm; 2.5g.

Description. This figurine is a very small standing human figurine with well-delineated features carved from soft limestone (Fig 82). On the head, ears are indicated and the face depicts eyes, a large nose and mouth. The torso is relatively broad with arms hanging down at the sides. The figure shows a protruding belly with a large belly button incised in the middle. The belly slopes down and outward, then cuts in straight to the groin. The thick legs are divided both front and back and have well-formed feet. On the back the leg divide proceeds up the buttocks, which also protrude outward from a very straight back.

Context. 11324.X3 derives from space 202, building 42 in the 4040 area. The unit has been interpreted as some kind of infilling or leveling event to the south of the bench in this space.

Discussion. This figurine is interesting both in terms of its miniature size and lack of clear sexual features. One other similar figure was recovered this year from the Istanbul surface scrape (11324.X3 Fig. 83). Such miniature objects can invite a much different range of use activities than the larger statuettes. While the latter are often (wrongly) envisioned as sitting in a shrine, being viewed but not circulated or handled, the former perhaps are more easily seen as more portable objects that can be carried, worn, exchanged, hidden, etc. The lack of any clear sex markers in these embodiments also compels us to reconsider the status of gendered representation within the figurine corpus. Although many take exaggerated buttocks and stomach to be indicative of femaleness, such features are necessarily ambiguous markers of sex. And we must consider the possibility that the emphasis of these traits invokes meanings beyond that of binary sex categories. Figurines whether sexed or unsexed may deal more with the exploration of identity and personhood than with categories determined or bounded by gender.

12401.X7

Dimenisions (H.xW.xTh.): 6.51 x 7.37 x 6.44cm; 221g

Description. This figure depicts a human, hybrid representation perhaps of life and death. The front portrays the typical robust female with large breasts and stomach (provocatively, the navel appears to protrude (umbilical hernia) which sometimes occurs in pregnancy); very thin arms with delineated fingers (see Ankara 79-251-65) fold up to rest on the breasts (see Ankara 79-803-65 and 10475.X2). The front base of the figure is missing but it appears to be seated with legs crossed in front (Ankara 79-20-65; 79-656-65). Red paint is present around neck and between breasts in four concentric chains (Ankara 79-20-65), and on the wrists and possibly the ankles. The trace of red paint in lower area suggests painted decoration seen on the ankles of other figures. The back portrays an articulated skeleton with a modeled spinal column, a pelvis and scapulas that project above shoulders. Individual ribs and vertebrae are depicted through horizontal and diagonal scoring. A prominent dowel hole indicates that originally the piece had a separate, detachable head. A circular ‘footprint’ around the dowel hole suggests that the head fit snugly into this curved space. The figurine was plastered and shows evidence of undergoing secondary burning (darkened clay/yellowish plaster), which is especially visible on the front from arms/breasts down and diagonally down sides where plaster is missing.

Context. 12401.X7 was found by the Istanbul team in an ashy area of space 252 with a large amount of ground stone, grinding stone, and a mace head.

Discussion. We have found no parallel examples for this piece across the site, the Anatolian Neolithic or the European Neolithic for that matter. The skeletal representation indeed seems unique, but even the style of the female body, with its exaggerated breasts and stomach, is different from other known Çatal examples that portray the female body in more naturalistic proportions. Given that the head is missing, we asked John Swogger to make a few Çatal types from modeling clay so we could get an idea of what the figure might have looked like with a head. The most interesting example was one modeled after the plastered skull found in 2004. He suggested a link between the plaster/skull and living body/skeleton couplings of the two representations. This led us to think more about the act of plastering which we will talk more about in the general discussion.

Unit (10396)

This unit is part of a primary midden deposit (truncated by a Roman foundation trench) in Space 268 in the 4040 area. Eleven figurine/ figurine fragments mostly comprised of zoomorphic forms (horns and quadrupeds) were recovered from this unit. One or possibly two abbreviated forms were also found (H3, H12). Most of these objects were recovered from screening. Only two X-finds were recorded. X1 is an obsidian point and X2 (Fig. 84) is a nearly complete standing quadruped with tail, R horn and rear R leg intact; all other legs are missing. There is a puncture mark through L horn x-section suggesting that the horn was intentionally broken off. Given the number of figurines found, this unit warrants closer examination.

Preliminary counts

The results of some basic object counts based on our new recording methodology are presented in Tables 2a–4b. As we are still in the process of refining our recording system, inputting unrecorded materials, sorting out exact numbers, and waiting for contextual information, these results should be taken as preliminary only. The counts were tabulated very quickly on site and there may be discrepancies among totals between different tables. We will sort these out later on when we publish a more complete and thorough analysis.

| Shaped Objects | Total |

Non-Diagnostic |

? |

Secure |

| Figural Objects | 999 |

233 |

111 |

655 |

| Non-Diagnostic Objects | 416 |

/ |

/ |

/ |

| Scrap? | 110 |

/ |

/ |

/ |

| Total Number | 1525 |

/ |

/ |

/ |

Table 2a. Overview of Shaped Objects

| Representational form | Total |

? |

Secure |

| Anthropomorphic (1) | 396 |

130 |

266 |

| Zoomorphic | 508 |

170 |

338 |

| Indeterminate | 205 |

0 |

205 |

| Geomorphic | 51 |

12 |

39 |

| Zoomorphic form | Total |

? |

Secure |

| Quadruped | 193 |

15 |

177 |

| Horn | 273 |

125 |

148 |

| Horn Types | Total |

? |

Secure |

| Horn | 273 |

125 |

148 |

| Straight Horn | 43 |

29 |

14 |

| Curved Horn | 175 |

57 |

118 |

| Anthropomorphic Forms | Total |

? |

Secure |

| Human | 120 |

15 |

105 |

| Abbreviated | 207 |

53 |

154 |

| Anthropomorphic Form Profile | Total |

? |

Secure |

| Abbreviated All | 207 |

53 |

154 |

| Abbreviated REC | 16 |

1 |

15 |

| Abbreviated Mellet | 22 |

4 |

18 |

| Abbreviated Current Excavations | 148 |

46 |

102 |

Table 2b Type and Subtype Profiles of Figural Forms

1. Anthropomorphic includes abbreviated forms.

Figural Type |

# |

# |

# |

9 |

8 |

8-7 |

7 |

7-6 (5?) |

6 |

6-5 (5?) |

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Anthropomorphic |

1 |

0 |

1 |

24 |

33 |

3 |

25 |

48 |

84 |

5 |

4 |

6 |

5 |

14 |

253 |

||

Human |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

9 |

0 |

6 |

5 |

30 |

0 |

2 |

4 |

5 |

11 |

76 |

||

Abbreviated |

0 |

0 |

1 |

15 |

16 |

3 |

15 |

33 |

23 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

115 |

||

Zoomorphic |

1 |

0 |

8 |

9 |

50 |

6 |

21 |

99 |

71 |

8 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

279 |

||

Quadruped |

1 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

27 |

1 |

8 |

45 |

35 |

8 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

132 |

||

Horns |

0 |

0 |

7 |

6 |

20 |

5 |

7 |

52 |

25 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

124 |

||

Total No. Figural Objects |

2 |

0 |

10 |

40 |

93 |

11 |

54 |

181 |

131 |

13 |

6 |

7 |

5 |

14 |

567 |

||

TOTAL No. Shaped Objects |

5 |

- |

# |

# |

## |

17 |

# |

313 |

## |

25 |

7 |

7 |

5 |

# |

- |

- |

830 |

Table 4b. Counts per Level

| Mellaart figual object profile | CHC (museum) |

MELLET (etutluk) |

REC (spoil) |

Total |

| Zoomorphic | 96 |

38 |

20 |

154 |

| Quadrupeds | 83 |

28 |

1 |

112 |

| Horns | 3 |

5 |

15 |

23 |

| Antropomorphic | 113 |

30 |

18 |

161 |

| Human | 65 |

5 |

1 |

71 |

| Abbreviated | 36 |

22 |

16 |

74 |

| Mellaart All (2) | 205 |

81 |

73 |

359 |

| REC Object Profile | Totals |

| Figurines, All | 47 |

| Figurines ? | 12 |

| Indeterminate | 11 |

| Scrap | 7 |

| Non-diagnostic | 17 |

| Total | 73 |

Table 2c. Profiles of Mellaart Materials including his Spoil heap (REC)

2. Totals include indeterminate and non-diagnostic pieces not presented in this table.

| Data Category | Count |

| Midden | 212 |

| Fill | 209 |

| Arbitrary | 47 |

| Construction / Make-up | 46 |

| Floor | 33 |

| Cluster | 14 |

| Activity (penning or burning event) | 7 |

| Natural | 1 |

| Total | 569 |

Table 3a. Figural Objects by Data Category